In the Opera House

key terms in context

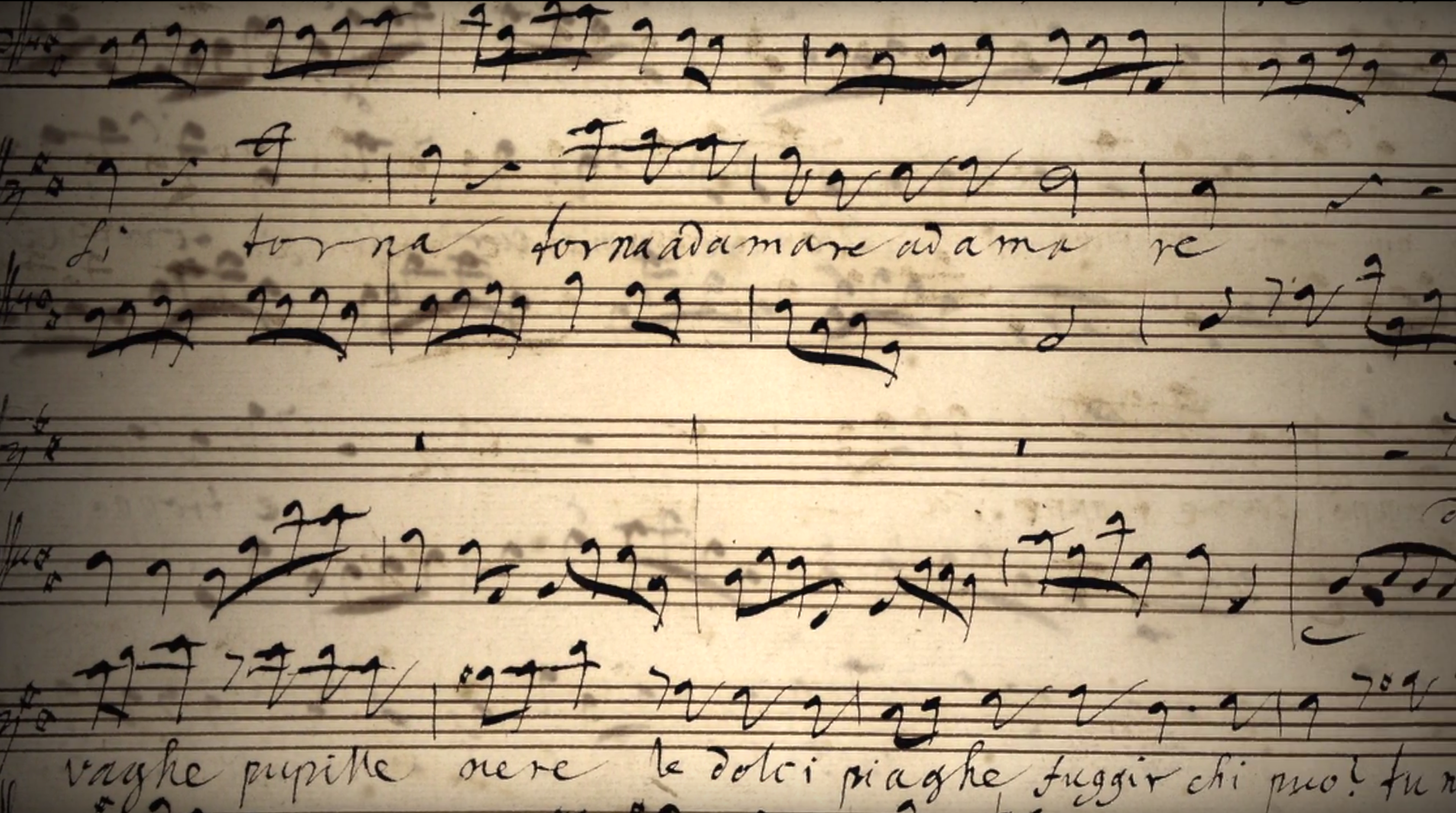

Aria – The songs of Italian opera, in contrast to recitative (see definition below). Arias were typically used to convey character emotions and illustrate the virtuosity of singers. The controversy around such virtuosity generated harsh judgments of Italian opera. Popular arias were often printed for people to learn.

Augustan – Writers who were the most prominent opponents of Italian opera in the early eighteenth century. Their designation as “Augustan” refers to their emulation of ancient writers during the rule of Caesar Augustus.

Judge / Judgment – In the seventeenth and most of the eighteenth centuries, those who critiqued music were known as judges rather than music critics, a term often employed derisively to mock someone’s musical judgment. My dissertation shows how the term and genre “musical criticism” emerged when musical judges felt increasingly pressured to analyze not just the stage but also the growing number of opinionated listeners.

Recitative – The plot-oriented dialogue of Italian opera, in contrast to arias (see definition above). Although recitative was sung and not spoken, it did not take the form of song, and was instead composed to imitate the rhythm and cadence of speech. The controversy around this style of composition generated harsh judgments of Italian opera.

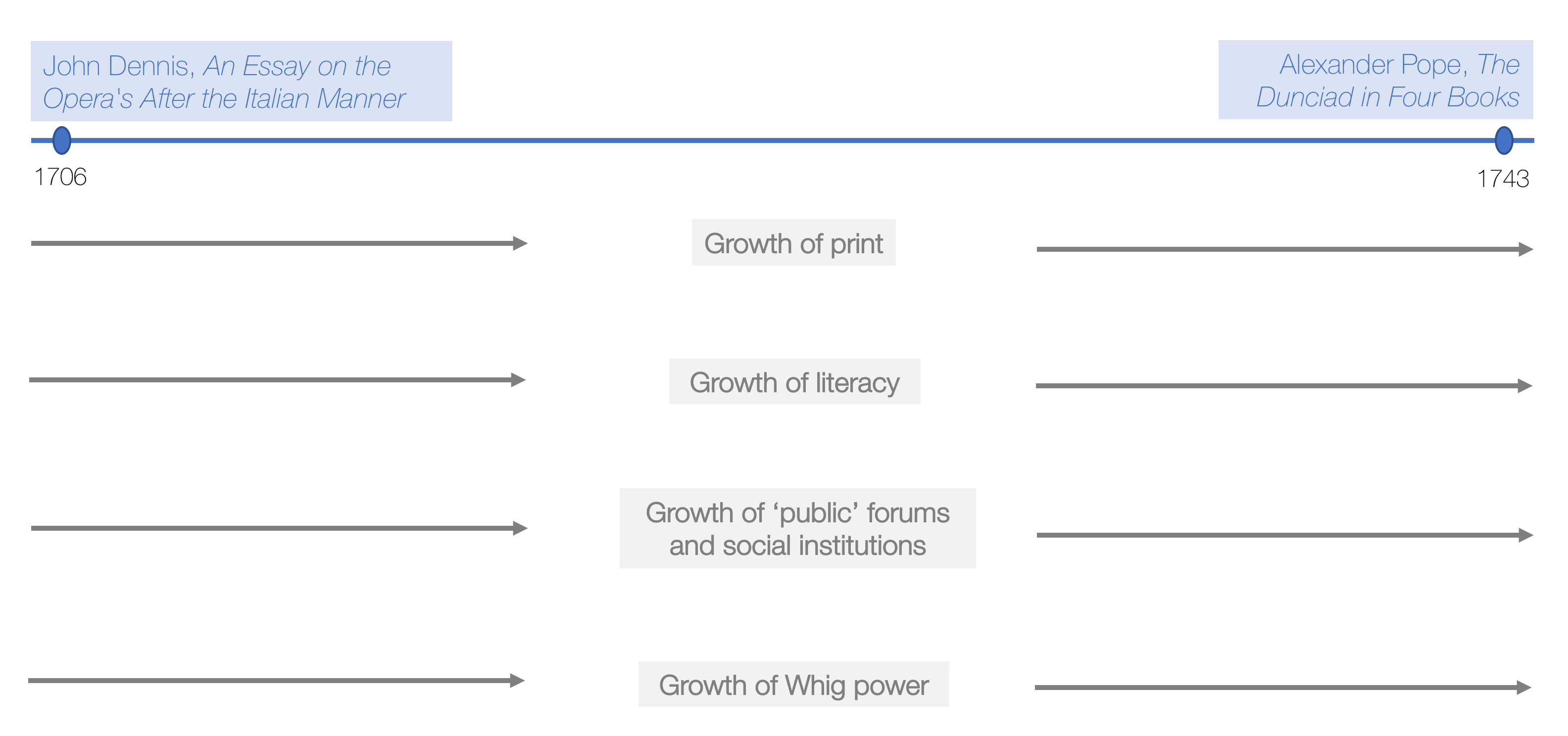

Whigs – The Whig political party held the majority of seats in British Parliament through most of the eighteenth century from 1715 onward. They comprised a large portion of the ticket holders and subscriber base for Italian opera performances. This intensified the politics of controversies over Italian opera.

Social, Political, and Economic background

The Opera House and Its Audience

English violinist and composer Thomas Clayton (1670-1730) is credited with first bringing Italian opera to the London stage. Debuting at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1705, Clayton’s Arsinoe, Queen of Cyprus became the first all-sung opera on the London stage – though sung in English, featuring Clayton’s musical setting of a libretto that had been translated from Italian. Whether his musical setting was wholly his own work or “pasticcio” – a patchwork of borrowed arias strung together with original recitative – remains debated, but its historical significance lies in its attempt to show the viability of replacing spoken dialogue with recitative in musical dramas.

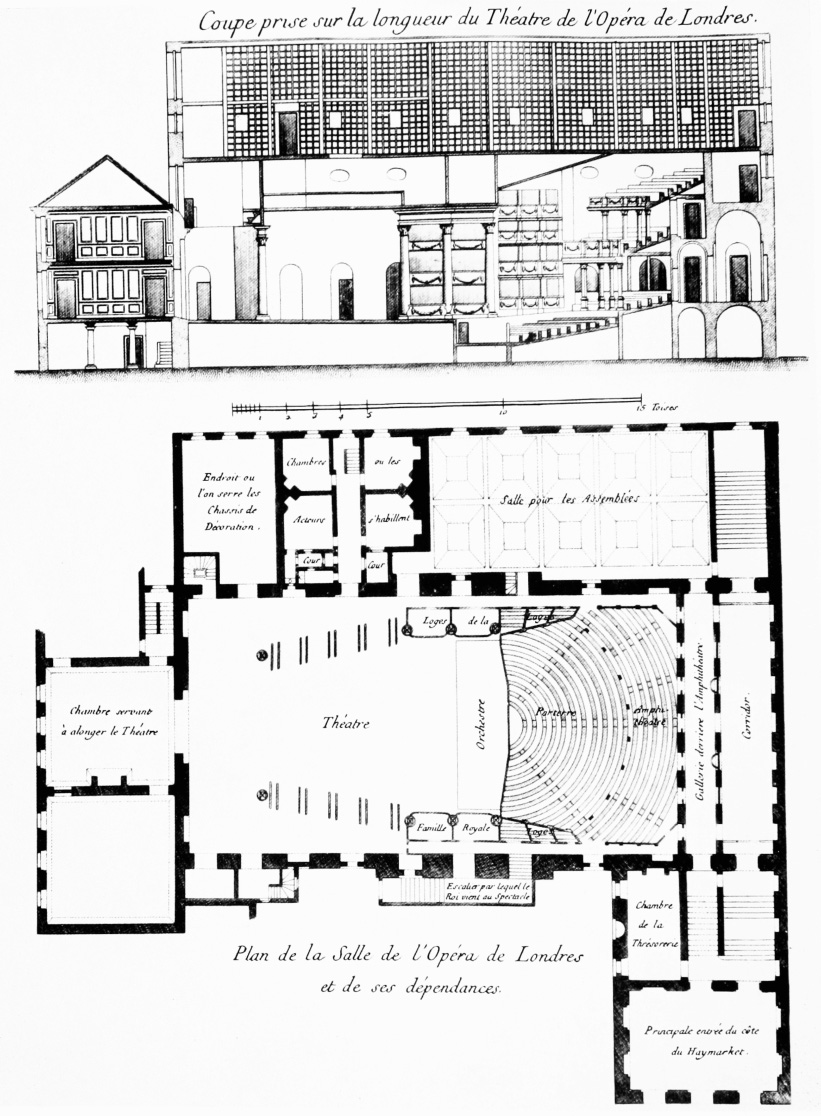

Italian opera found a dedicated home in the theatre in the Haymarket, which came to be known in common parlance as “the opera house.”

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Italian_Opera_House_at_the_Haymarket_(colour).jpg

The earliest surviving depictions of the interior come from Gabriel-Martin Dumont, whose Coupe prise sur la longeuer du Theatre de l’Opera de Londres (c. 1774) preserved an accurate representation of the opera house from the early eighteenth century [1].

Source: “Plate 26: Opera House, Haymarket.” Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster, Part 1. Ed. F H W Sheppard. London: London County Council, 1960. British History Online. Web. 27 August 2018. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols29-30/pt1/plate-26.

It was expensive to travel from central London to the Haymarket where the opera house was located. According to eighteenth-century theatre impresario and historian Colley Cibber, “The City, the Inns of Court, and the middle Part of the Town, which were the most constant Support of a Theatre… were now too far out of the Reach of an easy Walk; and Coach-hire is often too hard a Tax upon the Pit and Gallery” [2]. This can be illustrated by comparing the location of the main theatres in central London with the location of the opera house:

As a result, the many Londoners who frequented the theatres in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Covent Garden could not easily get to the opera house in the Haymarket.

In addition to travel expenses, the price of admittance to the opera house far surpassed that of the other theatres, reflecting higher overhead expenses such as exorbitant singer salaries and stage sets. Few could have afforded admission at the box office, fewer still advance subscription.

As a result, the audience members were mainly elites who exercised considerable power over productions at the opera House, determining which succeeded and which failed [3].

Judging Opera in Print

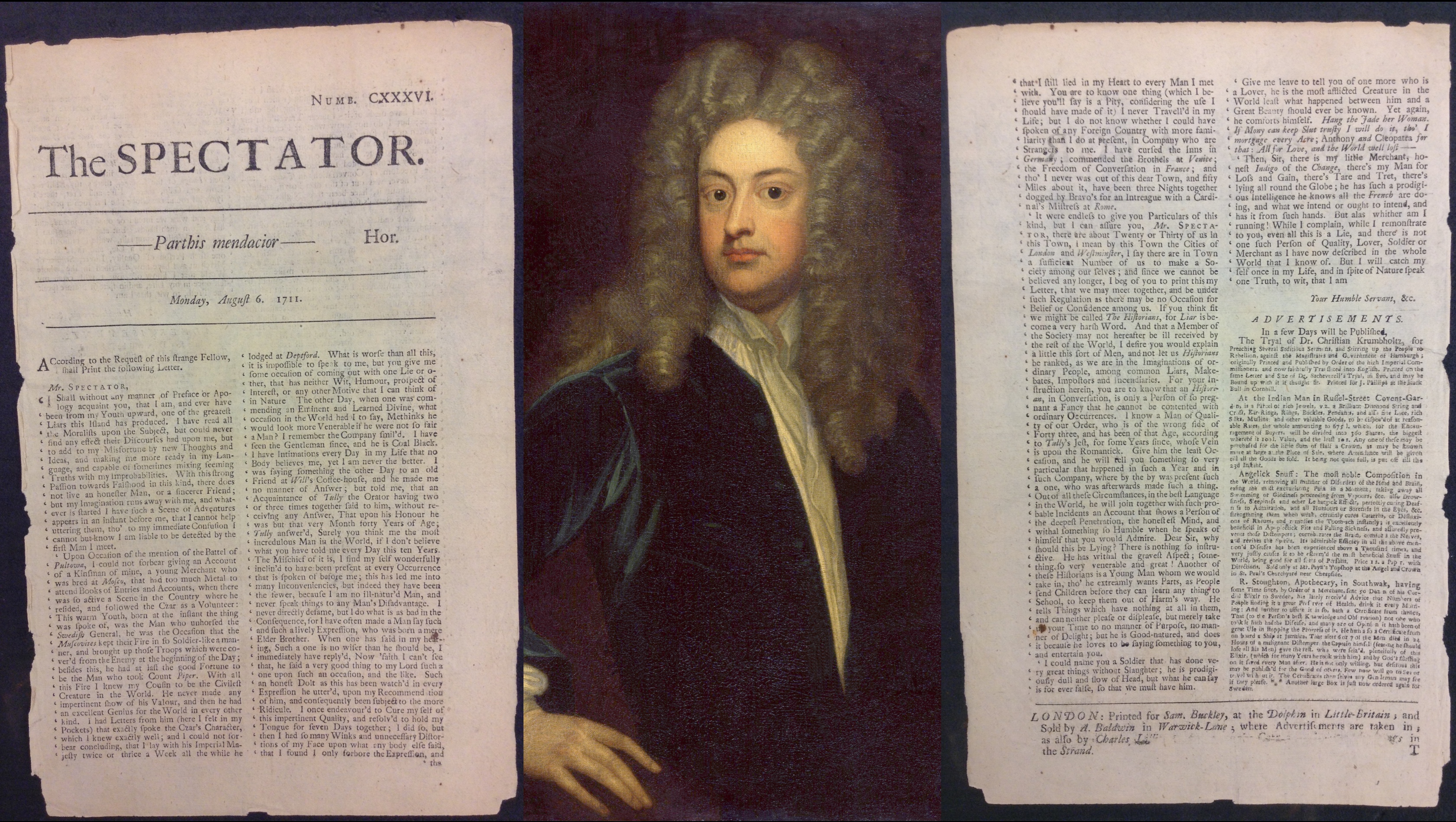

My dissertation, Sound Judgment: Ideologies of Listening and the Birth of English Music Criticism, argues that Britain’s Augustan writers — Joseph Addison, Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, and others — rejected Italian opera on the grounds that its foreignness rendered lay listeners incapable of comprehending, describing, and judging the genre. Joseph Addison illustrates this concern in his periodical, The Spectator, which he co-authored with fellow essayist Richard Steele.

Joseph Addison by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Digital reproductions of The Spectator. Sources: Fales Library, Wikimedia Commons

The Spectator uses the voice of its narrator, Mr. Spectator, to induce nervousness over Italian opera, in order to enlist reader support for reform of the genre. In doing so, The Spectator attempted to thwart the growing popularity of foreign-language opera on the London stage. Explore an example of this in the following Essay No. 5 in The Spectator:

The Controversial Sounds

The Spectator’s essays on Italian opera ridiculed key elements of the entertainment, but specifically its foreign language and opulent staging. In several of these essays, including Essay No. 5 shown above, The Spectator focuses on George Frederic Handel’s Rinaldo, a highly successful Italian-style opera which debuted in London shortly before the launch of the The Spectator in 1711. The following excerpt illustrates what Mr. Spectator was attacking both specifically and generally — in this case, the absurdity of mixing of “Shadows and Realities” by incorporating actual birds into the production.

Sources

[1] “The Haymarket Opera House.” Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster, Part 1. Ed. F H W Sheppard. London: London County Council, 1960. 223-250. British History Online. Web. 27 August 2018. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols29-30/pt1/pp223-250

[2] Colley Cibber. An Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber. London: Printed for R. Dodsley in Pall-Mall, 1750. 260.

[3] Daniel Nalbach. The King’s Theatre 1704-1867: London’s First Italian Opera House. London: Society for Theatre Research, 1972. 64.